The Trauma of Separation and Divorce

This article was authored by Deborah McKenzie, Program Manager,

Schools Services Program, at the Australian Childhood Foundation.

Over a twenty – year period in working as a school counsellor, I supported many young people whose parents were separating or divorcing. The trauma for these adolescents was palpable and often resulted in withdrawal and disengagement from school, avoidance of particular classes, avoidance of submitting homework, assignments or required assessment tasks, use and abuse of alcohol and other substances such as over the counter drugs (and those readily available in supermarkets), aggression, bullying, confusion, sexual promiscuity and risk taking behaviours that we had not necessarily seen with the young person prior to their parental issues.

It is easy to underestimate the impact of family arguments, parental separation, the leaving of one parent from the family home, the disconnection in relationships, the challenges extended family have when perhaps being prevented from seeing a child/young person due to parental acrimony. This leads to shock for a child and they may soon develop patterns of behaviour that disallow for constructive processing.

These can take any shape from excessive crying, bed wetting, hypo or hyperarousal, dissociation, anger and aggressiveness, endless and repetitive questioning, gastrointestinal issues, anxiety, depression, and respiratory constrictions and proneness to post-traumatic stress just to name a few. Whilst these behaviours might be a reaction to a short term event, research has clearly indicated that the long term impacts, if not dealt with effectively, are damaging for children.

School /education dropout rates can occur. “Evans, Kelly, and Wanner (2001 cited in Monash Literature Review 2003) also found that children from separated and divorced families were more likely to drop out of school, even when socio-economic factors were taken into account. Reasons for this higher rate of school drop-out and lower attainment levels include the adverse impact of parental conflict (including anxiety and depression); reduced parental encouragement, support and control; and less commitment from step-parents”.

Other long term impacts can impact: physical health and wellbeing, mental health (anxiety and depression), the unfortunate statistical correlation between children of divorce and their relationship successes into adulthood with the possibility of their own divorces, remarriage of a parent can affect family relationships and dynamics, economic/financial implications, and general resilience and wellbeing.

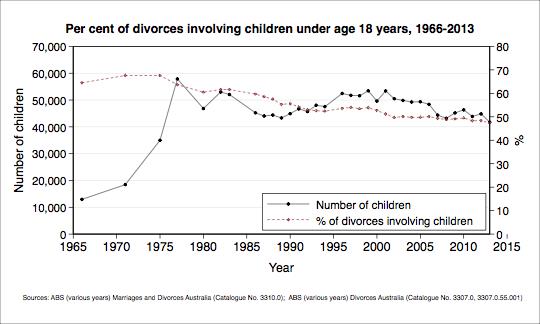

In 2016, there were 46,604 divorces granted in Australia. In 2013 there were 41,747 children under the age of eighteen impacted by divorce. (AIFS 2017).So much attention is often given to the needs of the adults at such times of family fracturing. Conversations between adults, which are in earshot of the children, may not be ‘contained’ conversations. They might be highly emotive, aggressive, accusatory or vindictive. Such conversations are conflicting for children as they do not share the feelings of one of their parents towards the other.

In 2016, there were 46,604 divorces granted in Australia. In 2013 there were 41,747 children under the age of eighteen impacted by divorce. (AIFS 2017).So much attention is often given to the needs of the adults at such times of family fracturing. Conversations between adults, which are in earshot of the children, may not be ‘contained’ conversations. They might be highly emotive, aggressive, accusatory or vindictive. Such conversations are conflicting for children as they do not share the feelings of one of their parents towards the other.

Children may not have an avenue for commenting on these or for processing the experience of them as they “were not supposed to be listening”.

Children can become fearful; constantly questioning and ruminating in their own minds what will happen to them, their siblings, their parents, the house, the finances, the school situation, and their friendship group. The world suddenly becomes unpredictable and uncontrollable and lacking in its possible consistency.

This makes life uncertain for the child or young person and can lead to their feelings of hopelessness, powerlessness, and helplessness in addition to their numbness with regards to the situation. This trauma of parental separation and divorce can ‘overwhelm their capacity to cope’.

A term that I am constantly challenged by is that of “broken home”. I hear this frequently in reference to a family that has experienced separation or divorce. The “that child comes from a broken home” comment is nothing more than a further labelling and potential shaming mechanism for the young person and sets them apart presumably from others who don’t have “broken homes”. What sense do they then develop about their identity and what narratives do they then attribute to their feelings of being ‘different’?

Victory (1993) contended that the nuclear family is only one type of family and its apparent demise is not indicative that the end of family life is imminent. Families come in all sorts of shapes and sizes and Eastman (cited in Weston 1992, p124) states that: “whatever family means by the family is what the family is”. So, is it “broken” or merely a different family form than what others might experience?

The question beckons then about how do we as practitioners, clinicians, therapists, and teachers, assist the child to disengage their traumatic shock patterns?

It seems that the answer is no different to how we would nurture any child or young person: to offer them safety, stability, a sense of belonging, a secure emotional base, knowledge that they are not ‘alien’ but more experiencing an extremely difficult life change.

It seems that the answer is no different to how we would nurture any child or young person: to offer them safety, stability, a sense of belonging, a secure emotional base, knowledge that they are not ‘alien’ but more experiencing an extremely difficult life change.

The child needs understanding not judgement, care, and compassion, relational connection not disconnection and empathy to alleviate their sense of shame at the ‘family failure’ and events that lead to any marital discord or parting. From where I sit, the child requires adults who may look at the change in their behaviour as indicating a possible fear state, a state of defensive and a place where there may well be a lack of trust.

It could be indicating a place where they just want connection (even if it is in maladaptive ways) as their parents’ emotional states may be getting in the way of their previous unconditional connection and attunement to their children.

It is important to allow the opportunity for the child to express their feeling state and to be able to narrate their experiences in order to assist in the making meaning of them. It would also be beneficial to work with the parents to support them in considering their child’s needs amidst such difficulty. Children require a positive relationship with both parents; where the parents treat each other with respect.

Cashmore (2003) found that there are three key messages to consider when working with children of divorcing parents. These messages came clearly from the ‘voice’ of the numerous children who were interviewed:

- Please keep us children informed when the family context is changing

- Please keep us children actively engaged and listen to our thoughts and ideas about decisions that have to be made

- Please allow us to have some flexibility in when we can see each of our parents

What do you see as the crucial support mechanisms for children experiencing the separation and divorce of their parents?

What modalities might one use to assist the children and young people to make meaning of their experience and to allow for their voice to be heard?

References:

https://aifs.gov.au/facts-and-figures/divorce-australia/divorce-australia-source-data#children